Article Contribution

Article by Ruth Smith, Mansfield News Journal. Sunday, January 7th, 1968. The following article is the first in a series of five stories in which Architect Louis Lamoreux recalls designing and building “The Big House” at Malabar Farm.

Louis Lamoreux

Occasionally leaning back….sometimes reaching forward from his chair to rummage into stacks of yellowed papers in his desk, Mansfield architect Louis Lamoreux probed memories of nearly 30 years.

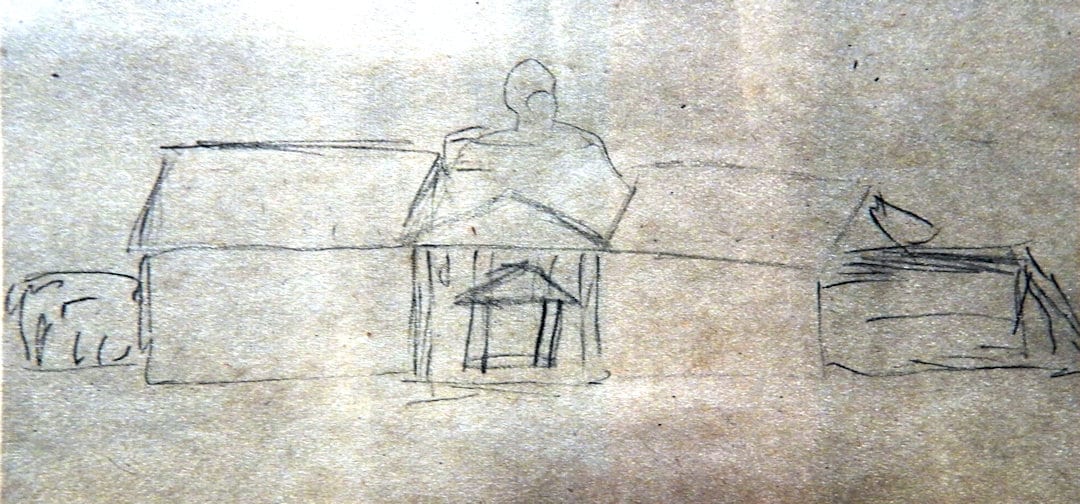

He wanted to talk about a home he had designed in 1939 for Mansfield author, the late Louis Bromfield.

He wanted to express the “just plain lonesome” feeling he had for Malabar, and the life, and some of the Bromfield possessions no longer in evidence in the Bromfield home.

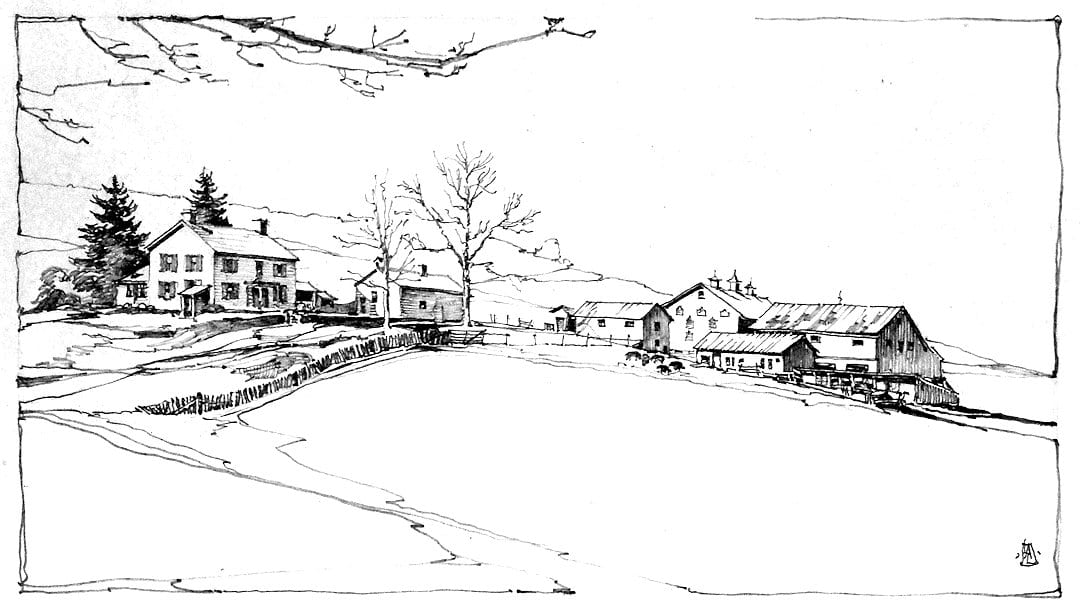

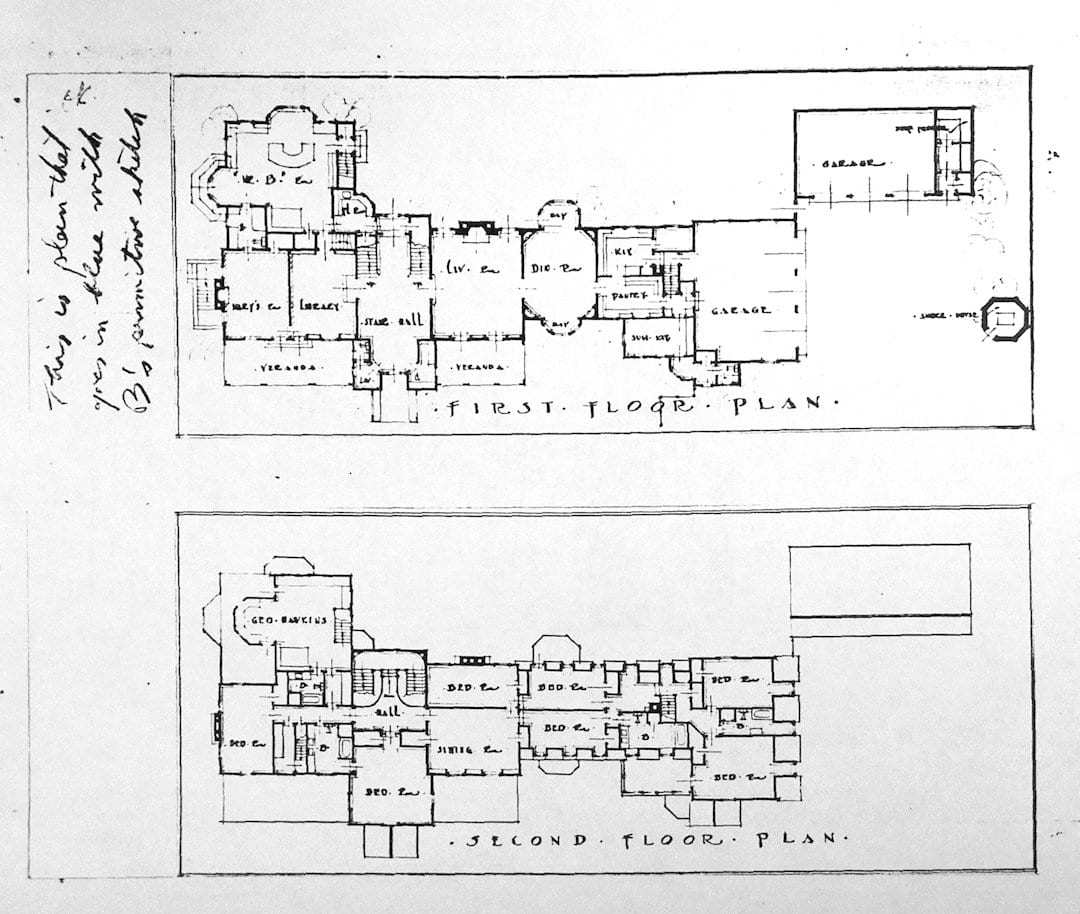

Bromfield asked Lamoreux to remodel an old farm house some 11 miles south of Mansfield….up Little Mountain Road. The finished product, an assembled house with parts of this and that from five periods of Western Reserve architecture became “The Big House”.

“Those of us who were fortunate in knowing the place, after its completion, miss now the very cluttered nature of each room”.

“Louis liked things that way,” Lamoreux said. “He seemed to abhor orderliness. He loved things used and with the aid of his dogs, many guests, children and the continual flow of activity, the place soon looked as if it had always been there.”

Lamoreux said he was “cognizant of the fact that when the place was sold, it was purchased “lock, stock and barrel. “We are not critical, “he said, “but just ill at ease, and often, as the late owner, just plain lonesome.”

Bromfield died March 18, 1956. A foundation now operates Malabar Farm.

With noticeable pride in his work of three decades ago, the architect said there “can be no question but that The Big House, like it or not, represents something that was never done before, and in all probability, will never be done again.”

With Bromfield’s consent, the original house was painted “a warm grey, as was so common in those days with people of discernment. “

“The multitude of detailed, authentic, early Western Reserve trim was all painted white, and through contrast,” Lamoreux said, “it simply sang and pleased the owner”.

Now they are almost lost in a poorly maintained drab mass of white.” Lamoreux said.

With irritation tingling his words, Lamoreux talked also about the barn door mural, and about the moving of the beds belonging to Bromfield and George Hawkins, the author’s companion and business manager.

“As Bromfield well knew,” the 72-year-old architect recalled, “it has been a longtime custom with Ohio barns to paint applicable murals on the barn doors.”

Bromfield brought up this detail one day, wanting something specifically “not arty,” Lamoreux said, and a “one Shorty Myers” who had been employed in painting “so called murals on the sides of nickelodeons” was put to work.

“The result was exactly what Bromfield wanted,” Lamoreux remembered, “for the cows had concrete legs, at least four of them, and the boxer dogs were frozen in place. It was all far from artistic….the fitting.”

“That bit of sentiment, effort and appropriateness are now gone…covered with more uninteresting white paint,” he added.

The architect then recollected that “Louis, as well as George, were adamant in that their beds be built into specified corners of their separate rooms. “Hell, no. Not on a dais, but in a corner surrounded by book cases and convenient shelves,” Lamoreux quoted Bromfield as saying.

Then he mused: “Certainly they were impractical for one had to get into the beds to them up, but who cared about that?”

And he asked, “Is there anything wrong about the retention “as was” of the original owner’s possessions?”

“They were an intimate part of him…his way of life when active and well….and he loved every part of The Big House half way up the hill.”